I've been lately working on implementing the "server" side of a TCP-based communications protocol for one of our clients that struck me a bit odd. The protocol itself is fairly simple, so that's not an issue; it's the messaging pattern that I found somewhat strange given the context under which it is used. To give you an idea of what that context is, here are some facts:

- The mechanism is pretty much request/response based: The client sends a message to the server, and expects a single message as a response.

- Messages are short, usually well under 200 bytes, ASCII-text.

- Each message has a fixed size header (opaque for us) and a variable-length body consisting of fixed-length fields separated by a known delimiter (that by itself is weird).

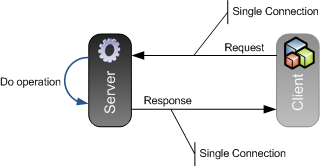

The messaging pattern for this protocol goes something like this:

As you can see, the message exchange is pretty ordinary: The client sends a request, and gets a response back from the server. However, the interaction (from the client's point of view) is asynchronous: The response is not sent over the original TCP connection, but instead it is received over a completely separate connection that the server (i.e. "us") opens to the client (i.e. "them"). In this sense, both parties are both servers and clients (peers) at a given point in time in the message exchange.

Nothing wrong with that. What's odd is that a TCP connection needs to be opened and close for each message sent in each direction, which is fairly inneficient, so to speak. So the client opens a connection, sends the message, and closes the connection; and the server gets to do the same on the way back. There isn't any sort of connection pooling or reuse going on.

That said, as I said the protocol itself is dead simple, it's just a little bit more work to do, and a little bit more error prone than it would be if all the exchange was done over a single TCP connection (just put a few firewalls and the atlantic ocean between client and server and you'll see why).

On interpreting specifications incorrectly

While implementing this I realized that I had originally misinterpreted the protocol specification. I initially thought that the response message was sent over the same socket the request had come in! Fortunately, once I was corrected in my assumptions, it was easy to change because of the design I had chosen for the server:

I had completely decoupled the class that accepted connections over the listening socket (the SocketServer) from the class that received the request message from the actual socket (the ServerChannel) and in turn that was decoupled from the classes that actually processed the message (RequestProcessors) based on the request type (all done using well-defined interfaces and taking advantage of Windsor container to hook everything up). So, I didn't need to change any of the message processors, and it was just a matter of adding a new channel class (the ClientChannel) and having the ServerChannel class send the response message through it instead of the original socket. Not bad at all, particularly with the NUnit tests I had in place for this!

A different protocol

A few years back I got to implement the client side of a somewhat different (and somewhat similar protocol). In this case, the task at hand was to connect to a corporate mainframe (a Unisys Clearpath server, as it were) to do things like extract client information from a central database.

In this case, the context was as follows:

- Every message had a fairly complex header included.

- The body was a simple positional stream of fixed-length fields.

- Messages were a bit longer, ranging from 200 bytes to about 1KB.

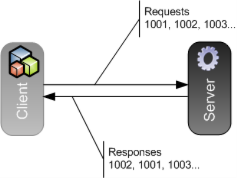

The message exchange pattern on this one was also request response, but also asynchronous in nature:

The protocol here was built around a single TCP connection (a session) that the client established with the server at the beginning. This was actually a telnet connection that after some simple negotiation (no terminal emulation, for example) was used as a full-duplex asynchronous channel.

While the protocol was request/response, the client didn't need to send a request and wait for a response before it could send the next one. Instead, it was built around continous communication: The client could just send request after request without pause, and at the same time listen for responses on the same TCP socket (the mainframe would just do the same as the client and send responses as they were generated from the underlying programs without pause).

Each request contained a four digit identifier that the client defined to identity the message, and the server would send the corresponding response with that same code when the response was generated, so the client could use the code to correlate a given response message it received back to the original request. Notice that there was no requirement that responses came in the same order that the requests were sent, and in fact it was possible that a request was sent and no response was received.

This was a little bit more complex to implement, but not too bad using separate sending and receiving threads, a request queue, a circular counter and a simple dictionary to match requests and responses. It also worked very well and was performance was pretty good (it helps that mainframes are pretty optimized for stuff like this).